For some reason I can't upload images to blogspot, so I've included links to the pictures at Flickr. With the exception of cars and trucks, and the occasional food item, by and large you don’t see American goods for sale here, at least goods that were made in the USA. What you see is a truly international market place where things such at toilet paper are as likely to come from Ghana as from China, where pots and pans are as likely to have been made in India as they were in Brazil, rice from Egypt or USA, and packaged food as likely to come from Lebanon as from South Africa. It is an international market place but also quite local.

[

Chinese Toilet Paper, repackaged in Accra, and bought at the side of the road.] At Keneshe Market, which specializes (if you can call it that) in food and fresh produce, I discovered the fresh meat section. Now for maybe a mile around Keneshe in all directions are thousands and thousands of market stalls, but inside the actual market it is much more concentrated and organized. First floor is food, the second floor is kitchen and household items, and the third floor, clothing, Ghanaian cloth, and 100s of seamstresses. In fact the sound of the third floor is the sound of 100s of sewing machines sewing. The third floor is where our bed sheets are being made, and the second floor is where I picked up the cheese grater that I wrote about in an earlier blog. Today’s journey brought me to the fresh meat section.

[

Dried Fish.]

Now as you walk around the first floor, you see lots of dried meat: fish, pigs feet and frozen chicken parts, and other things I couldn’t identify, even live chickens. But in a corner of this floor, occupying perhaps 25% of the first floor is the fresh meat market, though I had walked right past the entrance several times. The organization is different in this section. Instead of an open area set up with wooden tables, enclosed stalls or concrete slap, the floor is crowned, with small 5” gutters on either side. The tables are concrete and set back from the wall about two feet, there is no wasted space and only one path through this part of the market. The room is perhaps 60 feet by 100, and glancing around you might think that this was all there was, fresh fish, eels, tilapia, red fish, and even something that looked like cat fish, that was still struggling to breathe. Most of the other fish has been frozen, but still had that shiny fresh look about it. The fish smell is overpowering and everywhere I look people are smiling at me and saying “Hey ‘brunie, come look,” or “How are you ‘brunie?” “Aey Ya,” I say, “How are you?” replying with what I think is “I’m fine,” and then asking the same question back.

This is one of the places that I wish I had an optical camera that would show you what I saw because it is quite unbelievable, and I’m sure I would have trouble getting a camera in there as Ghanaians are quite funny about picture taking. I pass into another section and the smell changes to red meat, cow, goat, sheep, and others. The air is heavy with humidity and smells of blood. There are cow’s heads upside down, with the throat slit, upside down with a white ghost like look. The is color of a blood-less cow. I wonder if the Islamic influence forces them to display the method of slaughter, so that it is clear that the tradition has been followed to completely drain the animal before cutting it up. For some reason it is the teeth that bother me most. They are white, worn down, and stained, and my eye focuses on them first.

I am reminded of a few weeks earlier when Fox and I were in search of a specialized guitar cable and were taken by Eric the cab driver to the musical instrument section of Accra. Here we were walking along the city street with shops that displayed keyboards, large speakers, amps, mixers and “Givson” guitars (a play on the famous Gibson brand). While the cable was being made and we came upon this dead white cow, upside down, legs pointing up, and a crowd mulling around it. We stop to watch. A boy, not any older than my son has a knife and begins hacking at the legs. Soon people are walking by us with leg parts, a hoof, a joint, part of the tail, and man with a huge smile walks by and says “Welcome to Ghana” and disappears into the crowd. Again I wish I had an optic camera that could record these events to share. Fox had his new camera cell phone and so steals a picture, but it doesn’t do it justice. It is amazing.

When the crowd grows past us, we start edging back toward the store with the cable. I’m half tempted to try to get some of the meat just to see if I could, but it is time to check on the cable. The light has been off so they have had to go to another, where the light is on to build the cable and while we are waiting, Fox points down to the open air sewer, the liquid in it is now red. We are downstream from the sidewalk slaughterhouse.

But here in the Keneshe meat market there is no blood, only its smell. Huge slabs of meat rest on sheets of paper waiting to be cut by large smiling men waiting to cut them. I am near to losing it and force a smile, but it is thin. I smile at the butchers laughing with each other, sharing in my discomfort. “’ello ‘brunie, how are you?” They are dressed in dark, blood stained clothing, and know, maybe from the lines on my face, that this is nothing like I have ever seen before. “Welcome to Ghana,” one says to me.

I am overwhelmed by it all, and mostly unable to organize my thoughts coherently other than to relate it facts: I went to Keneshe, did you know there is a fresh meat market there? But no one wants to hear about it, especially at dinner. A week later, I am looking through the glass at the meat counter in the air conditioned food store we frequent. There are ladies behind it with spotless white aprons waiting on me. I think about Keneshe, and it occurs to me that that was such an honest way of buying meat. It doesn’t try to hide its source. Still, I have yet to buy any this way. I ask Emmanuel, our day guard about it: “What do they do with the meat at night?” “They put it away,” he says. “But where?” I ask and he is thinking I am asking another question. “There are inspectors, the meat is very safe, always there are inspectors who examine until it is finished.” I ask more questions until I learn that there is a huge refrigeration unit that the meat goes into at night, and as it comes out is inspected. It is just 9am when I am in the market that day and so I wonder at what time do they start unloading it?

[

Medina Market Street (boy on bicycle)]

Tomorrow we are having guests over for an American dinner, Chicken and Dumplings. Inviting people to eat is something that is done in Ghana frequently, though we have yet to get into the full swing of this. Tomorrow will be our first time. Last Saturday we were at our missionary friend’s home, Michael & Clare Mosley, for an “American BBQ.” There were many other missionaries from the greater Accra area there and I think we all appreciated the thick slice of Americana with grilled chicken, brownies, beans, rice, and bottles of Coke. It was amazing, and wonderful, and after dark we watched the film “Emmanuel’s Gift” outside on the wall of their compound using an LCD projector. Just as we were about eat the lights go off, and so there is the constant drone of the generator. Biting into a delicious chicken leg I wonder: did the chicken come from Keneshe? Our missionary friend Nicole Sims asks another question “Do you eat the bones?” She asks the Ghanaians sitting at our table, and they laugh. One of the women, says yes, but her husband won’t. After they were first married she tells about her husband seeing her eat the bones and asking, “Are you an animal that you eat the bones too?” They argue about it and she asks him, “Are you Ghanaian?” It is a custom not shared by all. Nicole asks how to eat the bones, and she says “don’t force it” Later as Nicole is biting into a breast bone, the woman cautions her: “Don’t force it!”

“Am I forcing it?” she asks with bones still in her mouth so it doesn’t come out clearly.

“I see your face” and she is right, it has that tight strained look, like I had walking around the market. A forced smile. I watch Nicole and I wonder if I’ll ever be able to eat the bones, or for that matter buy meat at Keneshe?

Later I wonder if that was part of the disconnectedness I felt in the states. That with the exception of hunters and fishermen, and maybe people who garden, or shop at the farmers markets, we Americans have become quite disconnected from the source of the food. “You are what you eat,” they told us in school, and so what happens when we eat food that is disconnected? Do we too become disconnected? Is that the problem?

It is not that I am suggesting that we close the meat counters and return to the open meat markets, or bring our grain to the grist mill to be ground, but I wonder if this disconnectedness is a symptom of a greater problem. In my last few years of ministry the running theme was one of connectiveness, and the catch phrase was “connecting to God, to other believers, and the one God made you to be.” I saw this then and still see it now as the grand purpose of the church. But that catch phrase didn’t connect so well with the people of that church no matter how many times I talked about it. It seemed to me that if we could just do those three things (connect people to God, to other believers, to the one God made them to be) then we would be the Church that God would bless us.

“Connecting to God, to other believers and the one God made you to be” was derived from a definition of sin that Robert “Bob” Tuttle, (professor of Evangelism at Asbury Seminary) gave in a revival at Oak Park United Methodist Church

[1] in the spring of 2001. He said that sin was “anything that separated you from God, from those around you or who God made you to be.” Being an expert on sin myself, I would have to agree, and so reversing this definition, I thought it made perfect since to see the purpose of the church as an anti-sin organization, in other words where sin caused you separation from God, the church would help you connect to God; whereas sin caused you separation from those around you, the church would help you connect to other believers; whereas sin caused you to separate from the one God made you to be, the church would help you connect to that person.

I thought that if I could model this for the church, and we did those three things—and only those three things—then we could change the world by living lives fully connected to it. Comfort and convenience were the problems I ran into, and how I preferred them over connectedness. Why call someone up when you could send them an email, or why visit them when you could call on the phone? When life is disconnected, one resists to doing things that better connect us to God, to other believers or even the food on our table. I was pushing a product I didn’t even use.

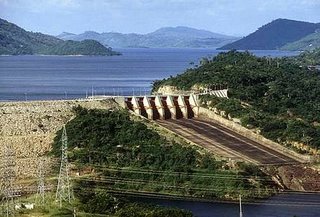

I wonder if that is the reason our lives in Ghana feel so connected. We have no choice, it isn’t always comfortable or easy, and when the lights go out, or we see a more direction connection to our food than we are used to, we are inconvenienced into realizing the connection. So tonight, as we prepare to be reminded that the Akosombo Dam, on the lower Volta river is still three feet below the minimum level, we will take our turn and lose the lights for 12 hours. Tonight, as my kids sit around the table doing their homework by candlelight, we will feel very connected.

But tomorrow night, when our guests come for Chicken and Dumplings, the light will be on and the chicken, it will come frozen from the store. Actually it comes frozen from Brazil because one of our guests is Muslim, and this chicken has been prepared in accordance to the Islamic traditions. It is how we connect to food that connects us to each other that connects us to the world and the international marketplace. I just wonder, will we eat the bones?

[

Islamic Center]

[1] Temple, Texas. Pastor was Andy Andrews at the time.