The Auto Parts Black Market

This week finds us preparing for next month, preparing for final exams; preparing for Christmas; and preparing to return the Patrol, which has been our transport these past four months. As you may recall the Jernigan, (Mission Society Missionaries here in Ghana) lent us their Nissan Patrol when Dr. Jernigan went to the UK to study tropical medicine, and Rev. Jernigan followed to take care of their kids. Sounds familiar, the Rev. following the Doc to take care of the kids. This SUV has been an amazing blessing and opened up parts of Ghana to us that we might not have seen, places like the villages Emmanuel took me to, the beautiful coast, the hills outside of Accra, and the Auto Parts Black Market.

This week finds us preparing for next month, preparing for final exams; preparing for Christmas; and preparing to return the Patrol, which has been our transport these past four months. As you may recall the Jernigan, (Mission Society Missionaries here in Ghana) lent us their Nissan Patrol when Dr. Jernigan went to the UK to study tropical medicine, and Rev. Jernigan followed to take care of their kids. Sounds familiar, the Rev. following the Doc to take care of the kids. This SUV has been an amazing blessing and opened up parts of Ghana to us that we might not have seen, places like the villages Emmanuel took me to, the beautiful coast, the hills outside of Accra, and the Auto Parts Black Market.On Monday, Emmanuel and I went looking for a lens. About week two of driving the Patrol, I backed into a garbage can and it put a crack in the left rear lens (or taillight). Today we have set about the task of placing it. First we went to the dealership where the Patrol was purchased, but they had closed, or moved, or were under renovations, or for whatever reason, the windows

were boarded up and they were not ready to receive us, or as they say, “we met their absence” so we continued looking. Just down street was Japan Motors, which also sells and services Nissans, but they too were under renovation. We stopped to ask in no less than six different departments (and buildings) at Japan Motors before finding the Spare Parts Department. Along the way we found the Service & Repairs department, and I asked if I could drop the car off for repair, but they told me I had to go buy the part first.

were boarded up and they were not ready to receive us, or as they say, “we met their absence” so we continued looking. Just down street was Japan Motors, which also sells and services Nissans, but they too were under renovation. We stopped to ask in no less than six different departments (and buildings) at Japan Motors before finding the Spare Parts Department. Along the way we found the Service & Repairs department, and I asked if I could drop the car off for repair, but they told me I had to go buy the part first.The part costs 1.86 million cedis, roughly $200. which was about what I was expecting, but Emmanuel thinks we can do better in the Black Market. So we’re off to fight traffic—it has taken us almost two hours to get to this part of town from dropping off the kids--or what I thought was traffic, but it turns out to be just a warm-up for the real traffic. The Black Market is one street off from Keneshi Market, a market I have passed by or been to several times. Who knew it was there? It isn’t a market so much as it is a street choked with parked cars, and lined with used car parts. The only thing that keeps the car parts from spilling into the road and blocking it is the gutter.

"Gutters" in Ghana

H

ave I told you about the gutters here? Some might call them open sewers, but Ghanaians call them gutters. These cement ditches are about one foot wide and 2 feet deep, sometimes they are six inches wide and two feet deep, other times 3 feet wide and four feet deep. Gutters line most city roads, usually on both sides and create a sort of reverse curb, and ever present danger of falling in one. I’ve actually stepped into one, but thankfully it was dry at the time. Gutters collect the rain, sewage, garbage, pee from men relieving themselves, children bathing in them, and just about anything you can imagine that could float or be washes out to sea. It is actually an amazing feat of engineering when you realize that every gutter was hand dug and is uphill from something, and whatever it collects flows to somewhere else. Mostly it floats or flows to Jamestown, the lowest part of Accra. Jamestown is home to one of the oldest prisons is Accra at the colonial Fort James. Next to the prison is the lighthouse, we visited some months back. That Saturday we were in Jamestown, the gutters were full and overflowing, and had quite an odor about them, which is understandable since this is the lowest point of the city, and all that sewage has got to flow somewhere. From here it flows out to the sea, and from atop the lighthouse, you can see its gray mixing with the blue seawater.

ave I told you about the gutters here? Some might call them open sewers, but Ghanaians call them gutters. These cement ditches are about one foot wide and 2 feet deep, sometimes they are six inches wide and two feet deep, other times 3 feet wide and four feet deep. Gutters line most city roads, usually on both sides and create a sort of reverse curb, and ever present danger of falling in one. I’ve actually stepped into one, but thankfully it was dry at the time. Gutters collect the rain, sewage, garbage, pee from men relieving themselves, children bathing in them, and just about anything you can imagine that could float or be washes out to sea. It is actually an amazing feat of engineering when you realize that every gutter was hand dug and is uphill from something, and whatever it collects flows to somewhere else. Mostly it floats or flows to Jamestown, the lowest part of Accra. Jamestown is home to one of the oldest prisons is Accra at the colonial Fort James. Next to the prison is the lighthouse, we visited some months back. That Saturday we were in Jamestown, the gutters were full and overflowing, and had quite an odor about them, which is understandable since this is the lowest point of the city, and all that sewage has got to flow somewhere. From here it flows out to the sea, and from atop the lighthouse, you can see its gray mixing with the blue seawater.

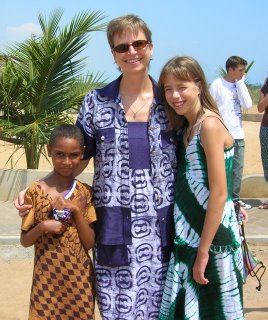

[Suzanne & Anna enjoy donuts in Jamestown, but look in the lower right and you’ll see full gutter. While that may look like an almost full ditch, there is actually 2 feet of sewage below.]

But our house doesn’t flow into the gutters, we have a septic system; but still we have gutters on our street and so each morning as I am backing out the car, I fear accidentally falling in to one. Once I saw a taxi accidentally back into a gutter as I was driving by (he fell off the gutter bridge), and I saw that telltale sign of blown tire, the blast of chalky air rushing out. The tire (or tyre as it is spelled here) was spoiled (as they say here). So gutters add interest to an already exciting driving experience, and here in the Auto Parts Black Market, I’m threading my way with maybe 10 inches of

wiggle room between parked cars, moving cars and the gutter.

wiggle room between parked cars, moving cars and the gutter.[Gutter bridge to our house]

Add to this the 100s of people rushing us from all sides. A boy steps out of the crowd, puts his hand on the hood (or bonnet as it is known) and blocks us. He directs us to park here. A parking space appears where there had be 20-30 men milling about in what looks like a parking lot, just off the street and over a gutter bridge. We pull in. As I do this I’m wondering how it will be getting out, but then more boys appear. “What do you want obrunie?” they ask. Emmanuel explains, and off they run, returning with man a bit younger than I, who is the lens specialist. He says come with me, and so we follow, and each step I take I see more and more car parts lining the street, transmissions, steering wheels, carburetors, exhaust manifolds, engine blocks. It isn’t like they have 1 or 2 they will have 100 of them stacked up in this unholy pile, and I’m wondering where they all came. The Patrol! Suddenly I have a vision of us getting back to where we had parked the Patrol and only finding a chassis frame, resting on the ground, the rest of it stripped (and for sale), and I’m wondering, “What would I tell Andrew?”

“Lets go back,” I say to Emmanuel and turn around. He follows and within minutes we’re back at the Patrol, except now there are two cars parked behind it and three in

front and now it would be impossible to leave. The man we had been following returns with a taillight lens, but it is the wrong side. “How much?” Emmanuel asks. “Four Million,” I watch as Emmanuel tells him he could get it at the dealership for 1.8. The man doesn’t budge on the price. A boy watching us runs his finger across the small dent in the bonnet. One time I had parked too close to a tree, and when the wind blew, it added a small dent. It was a month before I could confess it to Andrew, and by that time I had noticed some scratches on the inside of the windshield (or windscreen, as it is known), and thought the guards had done this cleaning it. I confessed in an email, and Andrew writes back:

front and now it would be impossible to leave. The man we had been following returns with a taillight lens, but it is the wrong side. “How much?” Emmanuel asks. “Four Million,” I watch as Emmanuel tells him he could get it at the dealership for 1.8. The man doesn’t budge on the price. A boy watching us runs his finger across the small dent in the bonnet. One time I had parked too close to a tree, and when the wind blew, it added a small dent. It was a month before I could confess it to Andrew, and by that time I had noticed some scratches on the inside of the windshield (or windscreen, as it is known), and thought the guards had done this cleaning it. I confessed in an email, and Andrew writes back:> The Patrol is HIS so don't worry. The scratches on the inside of the

> windscreen/windshield were there already on the new replacement

> that I got right before we left. It is covered with dents and scratches due

> to the roads to Amakom at the Lake and roads up north in

> church planting – so don't stress over a dent or scratch.

I must admit that my first thought when I read “The Patrol is HIS so don’t worry” was “Oh, great, now I’ve dented GOD’s CAR,” and how’s that going to look? But now there are greater things to worry about. Emmanuel is still arguing for the lens (and perhaps the car) with the black market auto parts dealer, and I’m thinking, “how is that going to look if I lose GOD’s car? Boys are gathering around, young men are leaning on the Patrol, and running their fingers across the paint and windows. The next day, when the night’s dust has settled, I see fingerprints all over it, like a CSI investigation. At the time it has looked like they were evaluating it, wondering what they could get for this part or that.

“Letsgo,” I say to Emmanuel, and off he goes to find car owner number #1, to ask him to move it. Now a third truck has pulled in behind cars #1 & #2, completely blocking the street so traffic is completely stopped. The mood of the place is changing, rising, and I think about locking myself in the car. I think about putting it in low four-wheel drive and making my own way out, ramming the cars that will move, and driving over the ones that won’t. Now, there is perhaps 30 men and boys milling around us, and it has the feel of a riot forming, pushing and shoving at me. The parts dealer is back showing me another lens. This time he wants eight million cedis for both lamps, he can’t just sell one, he says. This is the black market, so when did they start caring about rules?

I tell him no. “Why?!” he says.

“Because I can get it for 2 million at Japan Motors.”

“But you are here, eight million” and he points at the lens. I notice it is the left hand side, not even the one I need, but maybe that isn’t the point. Maybe the 8 million just to get out of here in one piece. I start praying, “I wonder how you’re going to get YOUR car out of here?”

I tell him “I will not buy this from you, it is too much”

“Eight million for both he says,” like maybe I didn’t’ get it the first three times, and I say “You’re crazy, I do not want both, and Japan Motors sells for 1.8.” You’re crazy. Did I just say you’re crazy? Can I even say something like that? What if he takes it wrong? What if he is insulted? So I smile widely, look him in the eyes, and take the lens he is holding and admire it. I hand it back and thank him for this very nice part he has shown us, but no I do not need. We shake, brother shake, shake again, and snap. “Good-bye!” He smiles and walks away into the crowd. The tension breaks, something has changed. The truck blocking traffic has moved, and driver from car #2 has just showed up and is backing out.

Now its only car #1 blocking us, but maybe two inches of spare room from the width of the Patrol and car #1. On the other side is the shell of a car that that clearly hasn’t moved for a long time, its car #0. What happened to that owner, I think. I get in and put it in reverse. I wish the Patrol had those back-up sounds, like industrial equipment, beep, beep beep.

Emmanuel stands in the street directing me, and blocking traffic. Everyone is motioning for me to back out more quickly, but I take my time. Isn’t that’s how we got into this mess in the first place? I manage to slip between car #1 and what is left of car #0, and then over the gutter bridge, and at one point I roll down the window to collapse the side view mirror as to avoid hitting a fence post. Then it is only a four point turn to miss the cars parked on the street, and the gutter and all the while not falling off the gutter bridge. Then I’m back on the road, with 100s of people, a gutter, and the parked cars, but at least we can move, and the Patrol is safe for now, and we’re unharmed.

“Lets not do that again,” I say when we hit the main road, and are thrust into a different sort of traffic. Emmanuel agrees, “I think Mr. Steve has gotten a very interesting driving lesson this morning.”

[bucket showers]

[bucket showers]

[the 4am Rooster, I'd prefer to change his name to "stew"]

[the 4am Rooster, I'd prefer to change his name to "stew"]