The next morning we were joined by ”Grace,” a friend of Emmanuel’s from Takoradi. It was an awkward paring, adding her to our adventures. For one thing she wore 3” platform heals, which really never make since, but considering how much hiking was a part of the programme, I’m sure she was regretting that choice by mid morning.

We went by shared taxi, then TroTro, then private TroTro, to Cape Three Point. Shared taxi is one that runs a regular route, in this case from Busia to Agona for about 60 cents. These taxis are small five passenger cars, which often hold seven uncomfortably. All day long he drives between these two towns and waits until the taxi fills up before leaving. If you are in a hurry, you can buy the empty seats, but that is no guarantee of a more comfortable or spacious ride.

The TroTro drops us at Akwidda, the town where the old witch cursed me [click here to read about that]. Now there is a derelict TroTro sitting where the curse happened, one that looks like it has not moved in years. Maybe the old witch cursed it too, I think. It is good to have a second chance at this place, an opportunity to pray over it and release the power it had over me. I looked for Stephen, the town drunk who had been our guide, but didn’t see him. Maybe just as well, as we picked up a different guide, who lead us across the bridge and up the hill to arranged for a private TroTro, one that just happened to fill with about 10 other people (who I am guessing rode for free).

All along that walk the kids shouted my friend, my friend, instead of the usual obruni. The people are friendly enough, they seem used to strangers walking through the intimate parts of their town, or to me it feels that way.

We were not comfortable at first, that feeling we had invaded their privacy, as the huts are so close together, and the doors and windows all open, it feels more like walking through hallways of a strange house.

Cape Three Point is the most southern point in Ghana and unique among the world’s capes. A cape is a pointed land formation that extends out into the sea, and as you can guess by the name, in this part of Ghana, there are three such capes, pointing into the sea, like three fingers, the middle one being the longest.

A lighthouse was built on it in 1875, and replaced 50 years later when the harbor of Takoradi was expanded by the British. In fact when I was in Agona, instead of being called obruni, the children called out to me Takoradi Obrouni, a remnant from that time when the British were building the harbor. In 2005, an NGO replaced the diesel generators that powered the lighthouse with six solar panels.

I can’t say enough about the beauty of this place is. I wish we could have spent hours there, just listening to the rage of the ocean as it threw itself against the base of the cape. I watch the waves crash, and wonder about what Emmanuel told me last night. We take pictures of him and Grace, and of me and her; there is a normality to what we are doing, that hides the evil he has planned. Denial is powerful ally, and yet I wonder, what is she doing here?

It seems oil has been discovered off Cape Three Point. Actually, it was discovered in 1982, so this is a re-discovery, but in 1982 they were not able to capitalize on it, our guide explains, there was a coup, Ghana’s fourth. Because it is so remote, Cape Three Point has been spared much of the over development that has plagued so much of the country. Development is not really the right word, more the devastation that a large population can inflict. But that all is about to change as they are planning to stretch a cable car from Kukum National Forest [click here] to this place, and soon the last remaining virgin ocean side rain forests will be opened up, and the protection of its remoteness, lost. I already feel that loss for this place, and how soon it will all change. Our guide doesn’t however, and speaks excitedly, and urges us to return in a few years.

It seems oil has been discovered off Cape Three Point. Actually, it was discovered in 1982, so this is a re-discovery, but in 1982 they were not able to capitalize on it, our guide explains, there was a coup, Ghana’s fourth. Because it is so remote, Cape Three Point has been spared much of the over development that has plagued so much of the country. Development is not really the right word, more the devastation that a large population can inflict. But that all is about to change as they are planning to stretch a cable car from Kukum National Forest [click here] to this place, and soon the last remaining virgin ocean side rain forests will be opened up, and the protection of its remoteness, lost. I already feel that loss for this place, and how soon it will all change. Our guide doesn’t however, and speaks excitedly, and urges us to return in a few years.

We walk back to the private trotro that has been waiting for us, and it loads with a different set of people riding for free. Back in Akwidaa, walk back to where the first TroTro had dropped us, and I see the derelict TroTro, but there are goats playing in it.

We walk back to the private trotro that has been waiting for us, and it loads with a different set of people riding for free. Back in Akwidaa, walk back to where the first TroTro had dropped us, and I see the derelict TroTro, but there are goats playing in it. Emmanuel explains that is our TroTro, and though I don’t believe him, I christen it the SS Derelict. He also says we have to wait for The Derelict to fill, so we have several hours to observe village life. I watch kids playing with stick tops, a fisherman repair his nets, and many men sitting under the large mango tree talking. This feels like the center of town, even though it’s the edge. The large tree defines the place, and you can understand why westerners mistakenly think Africans worship trees. On Sunday, Kwame-Michael Mozley asked the question in church “Do you know what happens under that tree?” I think back to the witch’s curse near the tree, to the men sitting under it and talking wildly, to the school age children drawing their letters on slateboard, or to the market. “Do you know what happens under that tree?” he asks again…”Everything.” What may seem like acts of worship are really just the living of life under the only good shade in town.

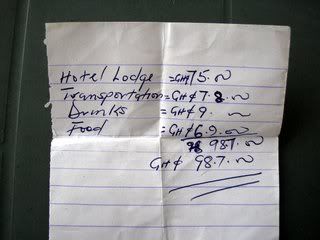

Emmanuel goes around trying to hurry the Derelict, but its a large one, so it is taking plenty, plenty time to fill. Grace is hungry, I give her some plantain chips I’ve carried from Accra, and my emergency water bottle. I look at Emmanuel walking around and think back to one of our earliest conversations, one where he told me it was his prayer that he would never do anything to lose my trust. “I know how you obruni are,” he said, “you value your money, and if you think you are cheated, you finished with us.” I’ve tried hard not to be one of those people he described, especially when I later discover he has added something to the bill, or kept the change, or quoted me one price, and next time when I do the deal myself, am quoted a much better price. I figure he must have added something to it and kept the difference. Suzanne thinks I am crazy to keep on doing things with him, but I figure it was just part of the adventures no one else would take me on.

I look at Grace. How uncomfortable she is, hot, hungry, thirsty, with sore feet. Later as I was telling Suzanne about it, I said “It was fascinating, wondering how it would all play out, knowing nothing was going to happen, no matter how Emmanuel maneuvered it.” We make small talk in the shade, she is a caterer, which means she has been to cooking school, instead of high school. She lives with her parents, her dad runs a TroTro yard, her mother is a nurse. She is maybe 20, Methodist, and later when we eat, she asks me to pray. People are now starting to move to the TroTro now, even though its in the full sun. They are taking the good seats and chasing the goats away. So we are taking the derelict.

We end up buying the last seat, except now the engine won’t start. I’ve been praying all day for God’s protection and wonder if this is part of that prayer answered, but then 10 men show up from under the tree and push, and push and rock back and forth, and 10 tries later, the engine roars to life and we are off. A few miles from Agona engine seizes and we walk the rest of the way.

For dinner its Groundnut soup again, but this time with fufu, goat meat and herring. I don’t eat bones this time.  “So what is the programme for the rest of the night?” I ask Emmanuel. It seems that Grace and he have been having a running conversation about me all day, she is saying I don’t think he will go through with it, or dance to the music as they say, and Emmanuel saying he will! Of course I’m oblivious to it all, they are speaking Twi. Emmanuel says, “You and Grace will go back to the Guest House and I will meet us in the morning.”

“So what is the programme for the rest of the night?” I ask Emmanuel. It seems that Grace and he have been having a running conversation about me all day, she is saying I don’t think he will go through with it, or dance to the music as they say, and Emmanuel saying he will! Of course I’m oblivious to it all, they are speaking Twi. Emmanuel says, “You and Grace will go back to the Guest House and I will meet us in the morning.”

“Emmanuel, I can’t do that,” I explain. “I’m a married man, and would never do that to Suzanne.”

“This is Africa, you must do this,” and I say, “I don’t think so.”

“Am I being too stubborn ? he asks. I don’t quite understand his meaning, stubborn is not how I would describe it. Immoral, deceitful, evil work for me, stubborn, not so.

“She is not coming home with me,” I say, and he is surprised. I remember this next thought, and make a mental note to add it to the premarital counseling I do. When you don’t feel committed to the person you are married to, then at least stay committed to the institution of marriage (FYI: Suzanne and I are getting along fine, it was just the thought that went through my mind).

“She is not coming home with me,” I say, and he is surprised. I remember this next thought, and make a mental note to add it to the premarital counseling I do. When you don’t feel committed to the person you are married to, then at least stay committed to the institution of marriage (FYI: Suzanne and I are getting along fine, it was just the thought that went through my mind).

Now we’re at the Takoradi Harbor and Grace has gone home. “So in your culture,” I ask when what I really want to say is WHAT THE @#$%^&* WERE YOU DOING!? “…in your culture would it have been alright to dance to the music?” He asks about the US culture, avoiding the question. I answer most would say no, but there are others that would dance to the music, but what about your culture? I wonder about the discipleship provided in the church he attends. Don’t they cover this? Emmanuel rambles on and doesn’t really answer the question, which is an answer in itself, I guess. I do learn he has a girlfriend there, one who is not his wife, nor the mother of his children.

I say, “Emmanuel, you have changed,” and I hear a weariness to my voice. I thought to earlier that morning, when we greeted his friends, how I could already smell apeteshi on their breath (apeteshi is distilled palm wine, like a strong Ghanaian moonshine). The night before I had noticed the alcoholic redness in the eyes of his friends. They are drunks, and I see traces of it starting in Emmanuel’s eyes. When I first met him he never drank, “Emmanuel, you have changed,” and I am sad. Sad for his wife Vida who taught me to cook, sad for Anna, his daughter who runs and jumps in my arms when I see her, and sad for Ruth, who is such a quiet flirt and had Malaria at the same time that my daughter Grace did. Mostly I am sad for Emmanuel, the path he has choosen, the future he may never have, and past he can’t escape.

Oddest moment in travel: being served Chicken and Gari foto, and a Voltic. Gari foto is a starchy Ghanaian side dish made with gari (dried Cassava) and red sauce; Voltic is the largest bottled water producer in Ghana. Second oddest moment: Anna and Suzanne dressed exactly alike and only discoverig it after all the bags were packed and loaded.

built up, but during the 1966 coup when even saying the word Nkrumah could get you arrested,

built up, but during the 1966 coup when even saying the word Nkrumah could get you arrested,

It seems oil has been discovered off Cape Three Point.

It seems oil has been discovered off Cape Three Point. We walk back to the private trotro that has been waiting for us, and it loads with a different set of people riding for free.

We walk back to the private trotro that has been waiting for us, and it loads with a different set of people riding for free.

“She is not coming home with me,” I say, and he is surprised.

“She is not coming home with me,” I say, and he is surprised.

Suppose I am from a village like this one and decide to leave against the recommendation of my elders.

Suppose I am from a village like this one and decide to leave against the recommendation of my elders.

Ju walks up the hill to her home to hug her kids, thank God for their safety, and pray for their protection.

Ju walks up the hill to her home to hug her kids, thank God for their safety, and pray for their protection.